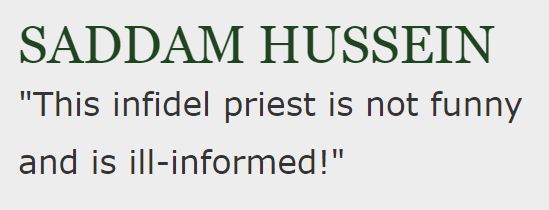

A Eucharistic Prayer is also called an Anaphora. While there is great variation among the various rites of the Catholic Church, especially in the East, until the Second Vatican Council the Roman Canon or first Eucharistic Prayer was exclusively used with certain variations for many centuries. While the stance for the prayer in many places (as in Spain, Italy, France and Mexico) is a combination of standing and kneeling (until the consecration); in the United States all but the priest are urged to kneel throughout. Pope Benedict XVI expressed his opinion in favor of the American option as a sign of reverence to the entire prayer. What we celebrate is something miraculous and appreciated by eyes of faith. The Mass brings us to Calvary. While the historical Cross of Christ is a bloody sacrifice; the Eucharist is a clean or unbloody re-presentation of that same one-time oblation. The unleavened bread and the wine are transformed through the words of consecration into the real presence of the Risen Christ, substantially present whole and complete in the sacrament of his body and blood. As Jesus taught the murmuring crowd of Jews in the Gospel of John, his flesh is real food and his blood is real drink.

The Roman Canon “as we know it” goes back to 1570 AD and the Council of Trent, albeit until recent times in Latin. Pope John XXIII added the name of St. Joseph to the prayer just as he was recently added to the other Eucharistic prayers.

While there are special prayers for children and reconciliation, there are four standard prayers that are regularly used. The Roman Rite emphasizes similar elements in each anaphora. This part of the Mass is sometimes called the “canon” as it is fixed and generally unchanging. While the pattern varies somewhat between the prayers, here are the common elements as ordered in the Third Eucharistic Prayer:

01. Praise & Thanksgiving (echoes the Preface and Sanctus)

02. Epiclesis (Invocation of the Holy Spirit)

03. Institution Narrative & Consecration

04. Memorial Acclamation

05. Anamnesis (Memorial Prayer)

06. Oblation Offered the Father

07. Intercession of Mary & the Saints

08. Intercession for the Church

09. Intercession for the Living

10. Intercession for the Dead

11. Concluding Doxology & Great Amen

The Mass is our most significant act of praise and thanksgiving. The reason why we should not miss Mass has less to do with the precept of the Church and what we will receive as it does with what we owe to God. Only with our priest can we offer this act of worship that most honors God. Those who stop attending because they “get nothing out of it” are failing to appreciate that the point is the other way around, what we can give or offer Almighty God— the gift of his Son and ourselves joined to him. This is the gist for the prayers of oblation to the Father after the consecration.

The epiclesis is the invocation of the Holy Spirit. It is by the Spirit of God that Jesus performs his miracles, heals the sick and wounded, and resurrects the dead. Indeed, Jesus rises from the dead by his own power, again the Holy Spirit. The same Spirit that conceives the Christ by hovering over the sinless Virgin will come upon the gifts on the altar. The priest will extend his hands over them. He will make a sign of the cross. Some of the Eastern rites will have the priest wave a cloth over the gifts, signifying the Spirit as the wind or breath of God. Note that the priest breathes or speaks into the cup for the consecration of the wine. The epiclesis and consecration are intimately connected in the overall liturgical action.

The words of consecration constitute a narrative; but more than historical, it is evocative. It is a command performance and our Lord tells his apostles, the first priests, to do this in remembrance of him. That which is remembered is made present. One might reckon the Mass as a sacramental time machine. We are transported both to the Last Supper and to the hill of Calvary. That is the meaning of Anamnesis. It is more than a nostalgic remembrance. The priest says, “This is my Body” and “This is the chalice of my Blood.” At the Last Supper cultic or ritualistic language is used. At the Mass, Jesus is referred to as the Lamb of God. We are told that a new and everlasting covenant is established. After the Protestant reformation, there grew a resistance to the reality of this sacramental mystery. However, it is no late Roman innovention. Many of the Jews walk away from Jesus because they find this teaching too hard to accept. They know that one could not establish a covenant with fake blood. Jesus means what he says. The transformation of the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ is later philosophically defined under the concept of “transubstantiation.” The appearance or the accidentals of bread and wine remain; but, the substantial reality is changed into the risen Lord, whole and complete in each particle and drop— his body, blood, soul and divinity. Bells may be rung at the epiclesis and at the two-fold consecration. Doubting Thomas becomes believing Thomas in confronting the risen Christ in the upper room. At the consecration my father like many others would echo Thomas by whispering his words, “My Lord and my God.” It is an act of faith in the Eucharistic presence. We encounter the risen Lord in the sacrament.

There are three options for the Memorial Acclamation, added to the words of the priest retained from the older form of the liturgy, “The mystery of faith.” The second acclamation makes a clear connection to the Eucharist: “When we eat this Bread and drink this Cup, we proclaim your Death, O Lord, until you come again.” The Anamnesis for the Third Eucharistic Prayer is as follows: “Therefore, O Lord, as we celebrate the memorial of the saving Passion of your Son, his wondrous Resurrection and Ascension into heaven, and as we look forward to his second coming, we offer you in thanksgiving this holy and living sacrifice.” In other words, what happened in time is now the focus of an eternal NOW. Connected to this oration is the Prayer of Oblation. Continuing with the third anaphora, we read: “Look, we pray, upon the oblation of your Church and, recognizing the sacrificial Victim by whose death you willed to reconcile us to yourself, grant that we, who are nourished by the Body and Blood of your Son and filled with his Holy Spirit, may become one body, one spirit in Christ.” We offer Christ and ourselves along with him to the Father. We enter into the Paschal Mystery of Christ and make it our own.

The Intercessions or Mementos are literally for those whom we are praying— we remember them. The priest quickly brings to mind those whom he is obliged to pray at the sacrifice of the Mass. Pastors are required to pray each Sunday for their parishioners. While there is insufficient time to recall many names with specificity, he likely has a general intention to pray for all those on his personal list remembered daily in the recitation of his breviary or the Liturgy of the Hours. There is no limit to such intentions; however Church law specifies that he can only take one paid stipend a day for an announced Mass intention. This is to avoid the abuse of trafficking in Mass stipends for remuneration.

The priest prays that the saints will intercede for us. We are asking that they pray for and with us. We want to be where they are. While we pray to and with the saints; the priest would also have us pray for the Church, for the living and for the dead in purgatory. The saints in heaven and the souls in purgatory are still attached to us as members of the Church. The Mass is an earthly and visible expression of the great heavenly banquet and the communion of the saints. We commend the souls of the dead and look forward to the resurrection of the dead intimated or prefigured in the glorified and risen body of Christ and in the uncorrupted body of Mary that is assumed intact with her soul into heaven.

While the dead in purgatory are helpless, we can assist them by our prayers, fanning the flames of divine love so that they might be perfected and sped on their way to heaven. It is by the fire of divine love that souls are purged of impurity and perfected for heaven and the beatific vision. We should not underestimate the value of the graces and fruits available to them from the Mass. If our loved ones should already be in heaven then these helps would be applied to some other poor soul who needs them and who has no one left in the world to remember him by name and to pray for him.

The Eucharistic Prayer ends with a doxology or hymn of praise: “Through him, and with him, and in him, O God, almighty Father, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, all glory and honor is yours, forever and ever.” The priest raises the Eucharistic Lord in the paten and chalice. The congregation responds, “Amen.” That “Amen” makes the entire action of the Eucharistic prayer, their own. The word “Amen” means many things— so be it— it is true— I believe.

We come to the Father through the mediation of Jesus Christ. He alone is the way. There is no other.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Leave a comment »